3, Sep 2024

What you could get in the Puerto Rican bodega: pantry staples and community

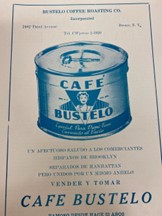

Walking down the streets of any of the boroughs in New York City, it’s impossible not to pass by at least one Puerto Rican bodega. Unassuming and quaint, these businesses offer a variety of food, from a simple loaf of white bread to Cafe Bustelo, coffee from the island. The presence of these mini grocery stores increased greatly in the mid-twentieth century, as Puerto Ricans migrated from the Caribbean to New York, seeking opportunities to start anew. In an attempt to carve out space for Puerto Ricans in New York, entrepreneurs arose from this community. They began with the simple corner store, or “bodega”. These commercial establishments served as not only a place to purchase food, but also as a backdrop for political conversations, and a symbol of Puerto Rican resiliency and permanence in the city. In a city that was diversifying quickly and delineating lines of racism and classism, Puerto Rican bodegas preserved the culture, language, cuisine, and essence of the island.

Puerto Rican bodegas, in essence, are stores that “have no more than 2 registers, sells mostly food and doesn’t specialize in any one item, such as candy or meat, and sells milk”[1]. These businesses, by definition, are inherently small, and their trademark has become compact shelves with almost every food category represented. This makes it a great stop on the way home from work for Puerto Ricans, or other New Yorkers, to stop for milk and light groceries on a regular basis. This also means that it also becomes a center for conversation and discourse among the Puerto Rican community. The everyday grocery store becomes a core part of any family’s life, but the bodega becomes an opportunity to reconnect. In a world where distance between farm and plate has grown, bodegas seek to shorten the distances between a family and their homeland by providing the flavors, sights, sounds, and people from the island.

Appearances and Offerings

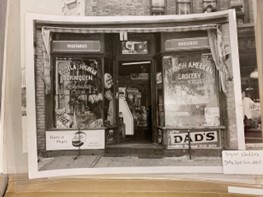

Bodegas have become iconic for their humble facades, iconic and integral to the urban landscape of New York City. Carlos Sanabria defines bodegas as “a small grocery store(s)…that began catering to New York’s Latino community in the 1950s and 60s.” Inherent to Sanabria’s definition, bodegas are a central small market that traditionally carries staples or versions of staples for Puerto Rican and Latin American households. In Figure 1 is a storefront of a Puerto Rican bodega in New York City. This is a quintessential example of the typical offerings; beyond that, the marketing done by these businesses to entice local Puerto Rican consumers is in their language – Spanish. At a time where families migrating to New York were struggling financially, storefronts that boast “buy here to save money” were extremely popular and attractive.

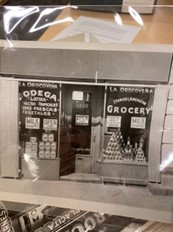

Figure 1: Puerto Rican Bodega Storefront ; Figure 2: Second Example of Puerto Rican Bodega Storefront

Moreover, while today’s bodega is characterized by its packaged foods, bodegas began as a place to get fresh groceries as well. The same figure highlights “fresh vegetables.” In Figure 2, ripe and unripe plantains line the windows. These along with beer, cigarettes and Café Bustelo made up the offerings of Puerto Rican bodegas. Even today, one can get fresh coffee, plantains, and baked goods at most local bodegas in New York.

Figure 3: Advertisement; Figure 4: Advertisement

World War II meant poverty and strife for many New Yorkers, but for Puerto Ricans migrating to New York with a goal to create a better life, it was an uphill battle. “The young and middle-aged Puerto Rican workers who migrated to New York around 1920 had come of age in Puerto Rico in a period of intense labor struggles”, and as the inequity in the labor market disproportionately impacted the minority communities, this also forced Puerto Ricans to channel their entrepreneurial spirit and start businesses of their own (Thomas 2018. 30). With thoughts of simple businesses that are ubiquitous and universally needed, as well as an emotional tie to an island far away, the bodega seemed like the perfect answer.

Othering

In both Figures 1 and 2, the signage reads “Spanish American”, seemingly referring to people who speak Spanish, not the true definition of Americans from Spain. But history has shown that Puerto Ricans were othered by New Yorkers for simultaneously not being foreign and not being from the mainland United States, and the way Puerto Rican bodega owners promoted themselves is a direct reflection of accepting that perception.

The fact that Puerto Rico was and is a commonwealth and not a state is something that is widely overlooked, even today. This resulted in an alienation of Puerto Ricans by New Yorkers, as well as hostility toward the community. New Yorkers saw Puerto Ricans “as just another immigrant group coming from a distant and separate country” (McGreevey 2018, 150). This belief was also weaponized politically by local governments. They would label Puerto Ricans as foreign to accrue relief cuts, or even use money to send Puerto Ricans back to the island (McGreevey 2018, 152). As poverty was being used to justify these repatriations, the need to achieve financial stability was paramount.

Puerto Ricans, as with many minorities, found themselves in a new city with a need to carve out spaces to be fully themselves. The need for these spaces, where they could be fully Puerto Rican can be traced back to a political debate that began in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. As the status of Puerto Rico, the island, was thrown into flux, so too was the status of Puerto Rican migrants to the mainland; should Puerto Ricans be “classified as ‘foreign’ or domestic” (McGreevey 2018,3)? This created a foundation for the racism Puerto Ricans would face as they made their ways to Philadelphia, New York, San Francisco, and other major US cities. It also created an opportunity for Puerto Ricans to be othered by not only white New Yorkers, but also other Hispanic-Americans who traveled from Europe or Central America.

Language

There are Puerto Rican specific words, however, on both windows: “La orocoveña”, speaking to a woman from Orocovis, a town in Puerto Rico, and “Borinquen”, a word derived from the Taíno language, of the island of Boriken, known more commonly as Puerto Rico. These are words that resonate with Puerto Ricans and speak to their culture. As a way of creating a safe space for Puerto Ricans making their home in New York City, both the foods and surrounding musicality of the Spanish language were prominent features of the bodega interior.

Bodegas would soon become not only a source of income for Puerto Rican families, but a safe space to express themselves, their culture, their food, and their language. Puerto Ricans made their way to New York City, many not knowing English at all. Just as their citizenship was questioned, their first language, Spanish, was also a point of contention among native New Yorkers. There is an assumption that upon setting foot on mainland soil, that you simply leave your culture behind and start anew as an “American”; “people are supposed to act like ‘Americans’”, and speak English (Vidal-Ortiz, 2004). But as Puerto Ricans step foot into a bodega, it is common to jump right into Spanish, or at the very least Spanglish, defying assimilation with a desire to maintain the Puerto Rican identity.

Spanish isn’t only present in the spoken words in bodegas; ads at the time displayed in these bodegas were also largely in Spanish. Ironically, New York City and State officials commented on the presence of these markets as an opportunity for native New Yorkers to get exposed to Puerto Rican food, but most of the advertisements, newspapers, and packaging in bodegas was and is in Spanish, reflecting that this may not have been the target demographic according to the bodega owners. Ironically, “Puerto Ricans, as a group, tend toward being bilingual”, but held steadfast in maintaining a Spanish foundation within the bodega (Vidal-Ortiz, 2004). Regardless of the location of these bodegas, be it in Harlem, Manhattan or the Bronx, these were spaces generally defined by their Puerto Rican-ness, language leading the way in that regard. In providing a safe space for Puerto Ricans to speak their language, bodegas create a mini-Puerto Rico within New York City.

Changes in language, much like adaptations in food, are typically a sign of assimilation; is the group that is“othered” attempting to blend in? With the frequency of Spanglish even today in Puerto Rican bodegas, one night assume that it was a desire to assimilate that caused this linguistic metamorphosis; however, one could argue that Spanglish takes up space, much like a bodega, in a way that gives the speaker the power to leverage two languages simultaneously, and still only be understood essentially by one group – the hispano-parlants. In the early era of migration, Puerto Ricans combatted (and continue to combat) discrimination and racism. Language was largely weaponized as a method of discrimination against the Puerto Rican community. Salvador Vidal-Ortiz speaks to the weaponization of speaking a second language, especially in New York City. An effort that originally sought to provide simple financial stability and tastes from home to Puerto Ricans in New York quickly became an embodiment of cultural persistence. This was evident to the point where various foods on the shelves, native to Puerto Rican cuisine or not, were labeled in Spanish; it is a language seen and heard, from the owners to the customers.

Community Growth

Neighborhoods populate with different cultural groups as firstly, they migrate to one particular place, but secondly as the area becomes more developed, it attracts others of the same group to join; “where they could feel connected to their experiences on the island (Vidal-Ortiz, 2004). As Puerto Ricans made their way to New York City, bodegas offered a comforting sign that they were near or among people from the island. As Puerto Rico is only three thousand five hundred square miles, it is also likely they had family already in the States or would come across family or friends in the city by chance, particularly at bodegas. While political discourse and activism will be discussed later, bodegas also were what they are today – a daily place of encounters with neighbors. Facilitating a sense of community was also an initial goal of the proliferation of these bodegas – in one small space, they offered a wealth of culture and family.

Bodegas became the epicenter of these neighborhoods in New York City, acting as a beacon to other Puerto Rican immigrants as a safe space. In a country that widely emphasizes the desire to assimilate, the “melting pot”, bodegas hold firm in their Puerto Rican identity. Their malleable language to create a new one, Spanglish, and their shelved packed with Latin American staples sparsely interwoven with American foods, reinforced the notion that Puerto Ricans were arriving in New York to add something to the city, not simply blend in. Despite housing a few “American” items, they predominantly offered Puerto Rican and Latin American food staples – shelves full of Goya, Bohio, and Bustelo line bodega walls. Their permanence over time illustrate the deep roots Puerto Ricans have in New York neighborhoods; bodegas are spaces that have generally remained unchanged, and that consistency is also a defiance in a country that continues to ostracize minorities. Not only this, but they have also become, despite that ostracization, a backbone to New York City’s economy and culture.

The specific inventory carried by bodegas may have been a reflection of the offering to the one or two European shoppers stopping by for a quick grocery shop, but it also could represent the evolving pantry of the Puerto Rican family in New York. Assimilation is a safety mechanism, and displaying these American staples can show that Puerto Ricans really are not that different from European or South American immigrants.

However, that safe space was also a strategic one, in spite of its evolving offering – this provided an environment where Puerto Ricans could speak their language freely, and conversations held in these bodegas were not always about inventory or simple small talk; political discourse and activism took place within the four walls of these small businesses. As they continued to battle racism, and marginalization by native New Yorkers and other Latin American groups, Puerto Ricans in New York began to mobilize and speak out. Artivism, as defined by Wilson Valentín, is “[the use of art to] respond to… social, economic, cultural and political alienation and invisibility; arguably, Puerto Ricans used a business based in food, a cultural expression, to protest and defy the status quo. And while there were formal demonstrations, letters, and protests, the simple act of running a business that refused to assimilate fully was an act of defiance in itself.

PRMA

These businesses had humble beginnings, with unassuming storefronts and foods most New Yorkers that were not from Puerto Rico would not recognize, but behind those doors, these business owners were strategizing to provide a better, more equitable life for their families. Thus in the mid 1940s, the Puerto Rican Merchants Association (PRMA) was founded. The meeting minutes of this organization largely focused on ensuring Puerto Rican businesses thrived in New York City. In its founding documents, the organization vows to “fiercely defend their community”[2]. These minutes, written in English, sometimes in Spanish, delineate conversations of the mid-twentieth century Puerto Rican community. These organized meetings led to political action; a protest was organized by the PRMA against a judge who had expressed anti-Puerto Rican sentiment in the mid 1950s.

Figure 5: newspaper article delineating the protest

Strategizing with their own public relations agent, they sought to publish their grievances with the New York Times and made their opinions heard. The financial stability, sheer volume, and prevalence of the bodega enterprise provided the foundation for such a powerful move by a minority group typically ostracized by its city.

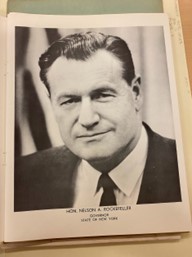

Figure 6: Nelson Rockefeller; Figure 7: Eugene Foley; Figure 8: Jacob Javits

In a city as vast as New York City, being heard by people in power is a huge feat. While individually these businesses are small, as a collective they possess a loud voice that reached the likes of Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Senator Jacob Javitz in the late twentieth century.

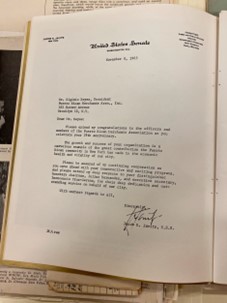

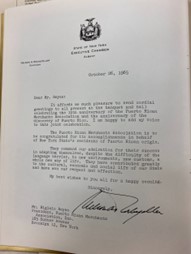

In the following two decades, the PRMA would continue to be a loud and powerful voice for the Puerto Rican community. In celebrating its nineteenth anniversary, the PRMA gained the audience and support of renowned politicians, including Eugene Foley (Assistant Secretary of Commerce), Rockefeller, and Javitz. As aforementioned, the idea these politicians had for the presence of bodega was as a cultural market that offered different foods to the typical grocery store, and that offered variety to other New Yorkers. Foley wrote in his congratulatory letter to the PRMA on its anniversary that “consumers will find new products to savor and enjoy.”[3] However, as these businesses began and expanded, Puerto Ricans were the most popular consumer at these bodegas. Moreover, Senator Javitz wrote in celebration of the PRMA’s 19th anniversary that it was important to celebrate the “great contribution the Puerto Rican community in New York has made to the economic health and vitality of our city”.

Figure 9: Letter from Jacob Javits to the PRMA; Figure 10: Letter from Eugene Foley to the PRMA

Other archival sources highlight the excitement of the “greatest ethnic market exhibit ever” in celebration of the PRMA’s 19th year. At this point in its history, notable personalities were celebrating the presence of the Puerto Rican bodega in New York City as both an ethnic entity and an integral part of New York City’s culture. Food merchants, artisans and craftspeople from the island celebrated Puerto Rican food and culture, front and center.

While letters from leaders of the time largely focus on a high level overview of Puerto Rican successes and their obstacles, letters from the President of the PRMA itself paint a more direct picture of the true challenges Puerto Ricans faced and still managed to overcome and form a successful business network.

Figure 11: Invitation to the PRMA 19th Anniversary, Higinio Reyes

Higinio Reyes, President at the time of the PRMA’s nineteenth anniversary, wrote in the invitation to the celebration that the Puerto Rican business owners “command our admiration for their success in adapting themselves, despite the difficulty of the language barrier, to new environments, new customs, and a whole new way of life”, seen in the letter, Figure 11.

Moreover, there was a famous Spanish market exhibit in New York City in 1964, The Spanish Market Exhibit. While largely for the local and state governments, this was an opportunity to promote Spanish businesses, the journalistic coverage intended for this event was going to be in Spanish speaking outlets. Again, for Puerto Rican Higinio Reyes, this was a chance to celebrate, on the anniversary of the discovery of Puerto Rico, the island and its culture, and continue the economic progress for Puerto Ricans in the continental US.

Figure 12: Second Invitation to the PRMA 19th Anniversary, Higinio Reyes

Today, the bodega has “prevailed as an integral part of the typical makeup of barrio culture” (Kaufman and Hernandez 1991, 3). “Bodegas provided a link to Puerto Rico,”; words written by Carlos Sanabria ring true, especially today. At its core, the bodega is not simply a business, but a window into a Puerto Rican kitchen on the island. One can certainly find a loaf of bread, a box of cereal that can be found at any grocery store, to be purchased in a pinch. But to walk into a bodega is a full-body sensory experience – one can smell the aroma of strong coffee, take in the bright colors of the Puerto Rican flag by the register, or hear the melody of the Spanish (or Spanglish) language, and find themselves transported to the warm Caribbean.

[1] New York City, Healthy Bodegas Initiative, 2010 Report

[2] Founding document written in the 1940s

[3] Special Message to the Puerto Rican Merchants Association, Eugene Foley 1965

Bibliography:

Bibliography

Henriquez. (2014). “La Feminista Nuyorquina” Contextualizing Latina Experience in the Space of Radical U.S. History: Dominican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban Presence in New York City. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Kaufman, & Hernandez, S. A. (1991). The role of the bodega in a U.S. Puerto Rican community. Journal of Retailing, 67(4), 375.

Lewis, Oscar. 1969. La vida: a Puerto Rican family in the culture of poverty–San Juan and New York. London: Panther Modern Society.

Luciano, & Haslip-Viera, G. (2019). Adjustment Challenges: Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1938-1945. The Writings of Patria Aran Gosnell, Lawrence Chenault, and Frances M. Donohue. Centro Journal, 31(1), 26.

Maldonado. (1997). Teodoro Moscoso and Puerto Rico’s Operation Bootstrap. University Press of Florida.

McGreevey. (2018). Borderline Citizens: The United States, Puerto Rico, and the Politics of Colonial Migration. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/j.ctt21h4w33

Rivera, Oswald. Puerto Rican Cuisine in America: Nuyorican and Bodega Recipes. Running Press, 2002.

Sanabria, Carlos. The Bodega: A Cornerstone of Puerto Rican Barrios (the Justo martí Collection). Centro Press, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY, 2016.

Thomas. (2010). Puerto Rican citizen history and political identity in twentieth-century New York City. University of Chicago Press.

Valentin. (2011). Bodega Surrealism: The emergence of Latina/o Artivists in New York City, 1976–Present. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Vidal-Ortiz. (2004). Puerto Ricans and the Politics of Speaking Spanish. Latino Studies, 2(2), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.lst.8600082

- 0

- By Amanda Leavitt

- September 3, 2024 10:00 AM